Killing God (read it anyway that suits you).

I am reading Julia Kristeva’s “Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia.” I have had mixed feelings about other works by Kristeva but I am finding “Black Sun” to be very insightful and helpful. She is engaging her own melancholia through the works of Nerval, Dostoevsky, Duras, the bible, and Hans Holbein’s painting of “The Dead Christ” (throw in Mother Teresa’s journal/diary “Come Be My Light,” and some tunes by Townes Van Zandt and I can think of no better company for our sufferings, doubts, prayers and tears).

This book was willed to me by a friend who died recently, within weeks of a very bad diagnosis, and like in Auden’s poem to the dead Yeats, it seemed that too quickly “...all the provinces of his body revolted.” In the chapter on Holbein’s “Dead Christ,” Kristeva has a black and white copy of Holbein’s painting, and there is a striking resemblance between my dying friend and the dead Christ (Holbein’s model was ‘...the body of a Jew who had drowned in the Rhine river’). There were many posting of Holbein’s Dead Christ on facebook over Easter and I have been reflecting on it again since then.

Kristeva references a well known passage from Dostoyevsky’s “The Idiot” in this chapter on Holbein but I want to offer this larger section:

“The picture depicted Christ who has only just been taken down from the cross. I believe artists usually paint Christ, both on the cross and after He has been taken from the cross, still with extraordinary beauty of face. They strive to preserve that beauty even in His most terrible agonies. In Rogozhin’s picture there’s no trace of beauty. It is in every detail the corpse of a man who has endured infinite agony before the crucifixion; who has been wounded, tortured, beaten by the guards and the people when He carried the cross on His back and fell beneath its weight, and after that has undergone the agony of crucifixion, lasting for six hours at least (according to my reckoning). It’s true it’s the face of a man only just taken from the cross—that is to say, still bearing traces of warmth and life. Nothing is rigid in it yet, so that there’s still a look of suffering in the face of the dead man, as though he were still feeling it. Yet the face has not been spared in the least. It is simply nature, and the corpse of a man, whoever he might be, must really look like that after such suffering.

I know that the Christian Church laid it down, even in the early ages, that Christ’s suffering was not symbolical but actual, and that His body was therefore fully and completely subject to the laws of nature on the cross. In the picture the face is fearfully crushed by blows, swollen, covered with fearful, swollen, and blood-stained bruises, the eyes are open and squinting: the great wide-open whites of the eyes glitter with a sort of deathly, glassy light. But, strange to say, as one looks at this corpse of a tortured man, a peculiar and curious question arises: if just such a corpse (and it must have been just like that) was seen by all His disciples, by those who were to become His chief apostles, by the women that followed Him and stood by the cross, by all who believed in Him and worshiped Him, how could they believe that that martyr would rise again? The question, instinctively arises: if death is so awful and the laws of nature so mighty, how can they be overcome? How can they be overcome when even He did not conquer them, He who vanquished nature in His lifetime, who exclaimed, “Maiden, arise!” and the maiden arose—”Lazarus, come forth!” and the dead man came forth? Looking at such a picture, one conceives of nature in the shape of an immense, merciless, dumb beast, or more correctly, much more correctly, speaking, though it sounds strange, in the form of a huge machine of the most modern construction which, dull and insensible, has aimlessly clutched, crushed, and swallowed up a great priceless Being, a Being worth all nature and its laws, worth the whole earth, which was created perhaps solely for the sake of the advent of that Being.

This picture expresses and unconsciously suggests to one the conception of such a dark, insolent, unreasoning, and eternal Power to which everything is in subjection. The people surrounding the dead man, not one of whom is shown in the picture, must have experienced the most terrible anguish and consternation on that evening, which had crushed all their hopes and almost their convictions. They must have parted in the most awful terror, though each one bore within him a mighty thought which could never be wrested from him. And if the Teacher could have seen Himself on the eve of the crucifixion, would He have gone up to the cross and have died as He did? That question too rises involuntarily, as one looks at the picture.”

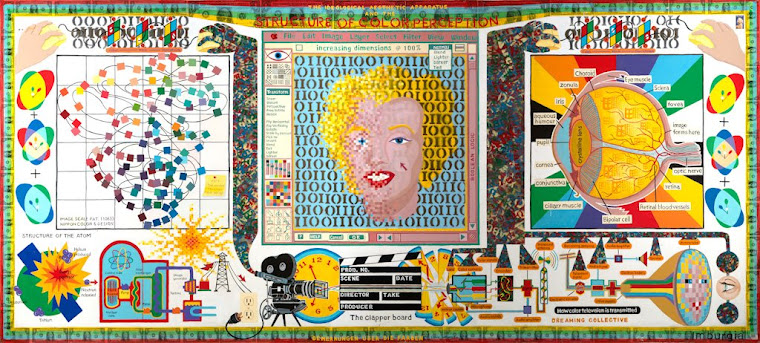

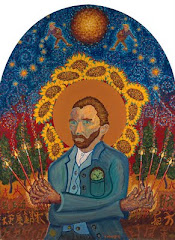

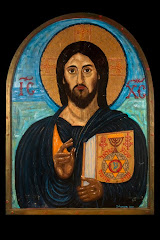

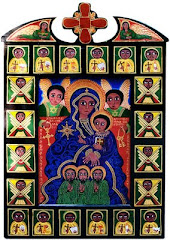

I have painted many dead Christs, but never any as startlingly realistic as Holbein. I think I am among those unbelieving believers that somehow try to avoid uncomfortable confrontations with actual death, the death of God, and let me say it more starkly, killing God. Yet I have seriously reflected on death from a young age, from the first death of someone I loved and that loved me. Still I paint traditional 2 dimensional Icons of idealized, sterile, even fanciful corpses. I’ve painted Impressionistic crucifixion scenes in the style of Chagall, Van Gogh, and even Kerouac, and some other more abstract even hyper-modern depictions, but none that look like a real dead person. I think this suggests a lack of maturity and maybe even integrity not only in my art but in my life and what rightly passes for my faith. The assertion of Christianity has been that Jesus really died, but I wonder if another part of Christianity wants to think of it more as a just a coma or a hibernation until one bright easter morning Jesus woke up, yawned, rolled the stone aside and like Neo in ‘The Matrix’, zipped off into the sky to do virtual battle in the ethernet until a parousia of our pixels reach an infinitude of density.

But if my art (or life or faith) cannot convince anyone that death is real, how could it convince anyone that life and resurrection is real? Prince Myshkin in “The Idiot” exclaims after seeing a copy of the “Dead Christ” in Rogozhin’s house, "That picture . . . that picture! Why, some people may lose their faith looking at that picture!" Many talk about a ‘life of faith,’ but should we also learn to talk about a life of doubt, despair, and destruction, or as Kristeva writes about mourning, a life of “naming suffering, exalting it, dissecting it into its smallest components” as a way to cope, to survive, to resist that “merciless, dumb beast” that seeks to ‘crush and swallow priceless being.‘ Stanley Hauerwas in his book “God Medicine and Suffering,” uses a similar phrase as Kristeva. Talking about the Psalms and how the church tends to avoid the Psalms of lament, complaint, darkness, and anger and focuses instead on the fewer happy/hopeful psalms, he suggests that part of the reason is that it is seen as unfaithful to embrace negativity, ambiguity, dejection and misery. I think it may also be a part of a all too typical dysfunctional family syndrome where no one talks about the violent, abusive, alcoholic, ultra-controlling father outside the home. Hauerwas says that the Psalms aren’t meant to help us deny and cover up our pain and confusion, but to give us a language to actually form an experience of despair and anguish, and that the Psalms “are meant to name the silences that our suffering has created.”

If I was writing about Holbein’s Dead Christ, I would say that it also named a silence into the painful reality of this world. But not that ‘god is dead...and we have killed him,‘ how tiresome and oh how much easier that sort of life would be, how redundant and uncomplicated, all our temples, shrines, icons, (and guilt?) replaced by microscopes and mirrors! No, Kristeva writes, “that faith be analyzable does not necessarily imply a method for getting by without it....” If your going to start mucking about looking for “meaning” best keep large amt’s of alcohol and Zanex on hand and get familiar with all the Psalms. I think that Holbein, Kristeva and Hauerwas would find some agreement in what Hauerwas quotes from Wolterstorff” “Suffering is the meaning of our world. For love is the meaning. And love suffers. The tears of God are the meaning of history.”

Psalm 38

2

LORD, do not punish me in your anger;

in your wrath do not chastise me!a

3

Your arrows have sunk deep in me;b

your hand has come down upon me.

4

There is no wholesomeness in my flesh because of your anger;

there is no health in my bones because of my sin.c

5

My iniquities overwhelm me,

a burden too heavy for me.d

II

6

Foul and festering are my sores

because of my folly.

7

I am stooped and deeply bowed;e

every day I go about mourning.

8

My loins burn with fever;

there is no wholesomeness in my flesh.

9

I am numb and utterly crushed;

I wail with anguish of heart.f

10

My Lord, my deepest yearning is before you;

my groaning is not hidden from you.

11

My heart shudders, my strength forsakes me;

the very light of my eyes has failed.g

12

Friends and companions shun my disease;

my neighbors stand far off.

13

Those who seek my life lay snares for me;

they seek my misfortune, they speak of ruin;

they plot treachery every day.

III

14

But I am like the deaf, hearing nothing,

like the mute, I do not open my mouth,

15

I am even like someone who does not hear,

who has no answer ready.

16

LORD, it is for you that I wait;

O Lord, my God, you respond.h

17

For I have said that they would gloat over me,

exult over me if I stumble.

IV

18

I am very near to falling;

my wounds are with me always.

19

I acknowledge my guilt

and grieve over my sin.i

20

My enemies live and grow strong,

those who hate me grow numerous fraudulently,

21

Repaying me evil for good,

accusing me for pursuing good.j

22

Do not forsake me, O LORD;

my God, be not far from me!k

23

Come quickly to help me,l

my Lord and my salvation!

Obliged.

Oh, let me add this form the Lars Von Trier movie “Melancholia” (2011) with Kirsten Dunst as Justine and Charlotte Gainsbourg as Claire.

ReplyDeleteJustine: The earth is evil. We don’t need to grieve for it.

Claire: What?

Justine: Nobody will miss it.

Claire: But where would Leo grow up?

Justine: All I know is, life on earth is evil.

Claire: There may be life somewhere else.

Justine: But there isn’t.

Claire: How do you know?

Justine: Because I know things.

Claire (angry): Oh yes, you always imagined you did.

Justine: I know we’re alone.

Claire: I don’t think you know that at all.

Justine: Six hundred and seventy eight. The bean lottery. Nobody guessed the amount of beans in the bottle.

Claire: No, that’s right. Justine: But I know. Six hundred and seventy eight.

Claire: Well, perhaps, but what does that prove?

Justine: That I know things… and when I say we’re alone, we’re alone. Life is only on earth… and not for long.